This is

one of the most common clinical presentations when it comes to distance

runners. These cases are often long and drawn out, with patients often bouncing

from one health care professional to the next.

One of the most vital pieces of information I can give to the patient is

that of education on the possible causes, management and treatment. Education

allows the patient to become active in the rehabilitation protocol.

Brief

Anatomy

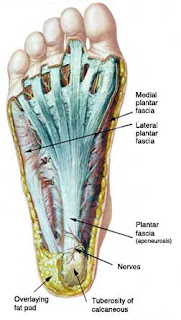

The

plantar fascia is a thick band of connective tissue with investing layers from

the calcaneal (heel) tuberosity to the base of the metatarsals, creating a

mobile yet stable soft tissue foundation for the medial and transverse arches

of the foot.

The

plantar fascia is composed of type 1 collagen

(a thick protein arranged in parallel bundles) with the ability to

resist high loads of tensile stress. It is considered a non-contractile tissue

responding to the mechanical loads placed upon it. It has poor ability to

stretch much beyond 4% of its resting length. The plantar fascia is prone to

degenerative changes in response to chronic overuse and increasing with age

related changes in the connective tissues.

There are

3 nerves that travel through the various layers of the plantar fascia from the

medial (inside) portion of the ankle. The medial calcaneal nerve, the lateral

plantar nerve and the medial plantar nerve all arise from the larger tibial

nerve. These often play a role in plantar fascia pain with the medial calcaneal

nerve often commonly involved as it wraps around the tuberosity.

Anatomy of the plantar fascia

Function

The

plantar fascia maintains the longitudinal and transverse arches of the foot and

also serves to dampen pronation. As the foot contacts the ground and continues

through to mid stance the plantar fascia lengthens under load almost causing a

breaking effect, thus absorbing load. This sets the stage for the foot to then

supinate creating a more rigid structure for toe off.

If the

plantar fascia undergoes degenerative changes (collagen disarray, neovessel in

growth, fibrosis etc) the structure become less mobile and less resistant to

tensile load. This creates further overload on already compromised structure.

Onset

Plantar

fascia pain usually appears with a gradual onset. Initially there is stiffness

(and pain) on arising only to warm up 5 minutes later. The pain gradually

progresses to pain on warm up and sometimes warm down. There is often a period

of weeks to months where the patient does not seem to regress. Often

this is where the running athlete does not present for treatment thinking “it’s

not getting worse!”. Despite no notable regression the connective tissue may

still degenerate under repetitive loads.

Over time

if the athlete continues to run there will be a point where pain is constant

through out the run. This is usually the first time a clinician will see the

runner often months into the process.

Causes

The

causes are likely multifactorial:

- Increase

in volume

- Increase

in intensity

- Change in

training surface

- Change in

footwear (or lack of)

- Reduced

dorsiflexion

- Excessive

pronation

- Reduced

great toe extension

Pronation – a possible causative factor

Prognosis

The

prognosis for plantar fascia pain is less reliable than for a straight - forward

muscle tear. The quicker the injury is addressed the better the outcome.

Plantar fascia pain is similar to a tendinopathy in nature, with degeneration

of the connective tissue a classical finding under ultrasound. Depending on the

location within the plantar fascia, will depend on the type of tissue you are

dealing with. For example, a degenerative enthesopathy (insertion onto the

tuberosity of the heel) will involve various connective tissues, possibly fat

pad and underlying soft tissues. If the focus is in the body of the plantar

fascia it may be a case of the connective tissue composition (type 1 collagen).

If

addressed early, clinical evidence would suggest you may be looking at 6-12

weeks recovery.

Chronic

ongoing plantar heel pain injuries can be as long as 6 months to 2 years with

high re-occurrence rates.

“The Doc

says I have heel spurs!”

A basic

understanding of the anatomy helps to understand the pathogenesis. As stated, the

plantar fascia attaches to the calcaneal (heel) tuberosity. In some cases

abnormal mechanics may place an increased demand upon the attachment leading to

an increase in bone loading, hence, size of the tuberosity.

There is

no evidence to suggest that an increase in bone (the so-called heel spurs) is a

causative factor in pain. In fact some asymptomatic patients (no symptoms) have

enlarged calcaneal tuberosities. It is therefore important to look to the

causative factors and ways of managing plantar fascia heel pain. A ‘spur’ is

not a sign of plantar fascia pain. The painful site is usually close to the

attachment and may be involved in some cases.

Treatment

Plantar

fascia pain presents in a similar fashion to a tendinopathy and as such should

be treated as one. There is little evidence to suggest inflammation to be a

factor in plantar fascia heel pain. In this case the treatment protocol will be

lengthy. Addressing the causative factor(s) is paramount.

Treatment options include:

Soft

tissue therapy to focal areas of thickening especially in the posterior lower

limb if reduced dorsiflexion is a factor. Joint mobilisation and local stretching may

improve the outcome. Clinically local soft tissue work to mobilise thickened areas

within the plantar fascia may be warranted.

Controlling

excessive pronation with strengthening of tibialis posterior (inside of calf)

and gluteus medius (lateral hip) or with the use of orthoses. Biomechanics

during the gait cycle may have an important role to play. Overall reducing load

on the plantar fascia. Low dye taping may help in the short term as a means of

gaining proprioception and further reducing load

Further

soft tissue treatment may help with overloaded structures (areas of increased tone)

that alter gait as a compensatory mechanism or as a cause of the injury itself.

Address

footwear* (or lack of – think barefoot running) - this is a hot topic at the

moment! Whichever way you decide to go, make it a slow transition and be sure

to use progressive over load and recovery techniques in your training program.

Consider

consequences further up the chain eg; reduced torso rotation can create

compensation through increase rotation of the femur, tibia and pronation. The

net effect is loading of the plantar fascia. Consider the whole kinetic chain.

Low dye taping may help

What about rolling on a golf ball?

This may

work to minimise the symptoms temporarily, however it will do little to help

with the driving factors. Very rarely do we find in clinical practice the

plantar fascia to be tight. It is important to consider the anatomy and

function when considering the goal of any treatment. The plantar fascia is a

thick piece of connective tissue with very little stretch – do we really need

to try and stretch it?

Is it always plantar fascia involvement?

This

discussion has focused on pain in the plantar fascia. There are numerous causes

of pain in the plantar surface of the foot,

the location will be a key to further possibilities such as:

- Fat pad

contusion (heel)

- Plantar

fascia tear (grade?)

- Sesamoiditis

- Morton’s

neuroma

- Stress

fracture of the cuboid

- Stress

fracture of the calcaneus

- Medial

calcaneal nerve compression (common)

Summary

Plantar

fascia pain is common in runners and often lengthy to treat. By the time the

running athlete has presented to healthcare professionals there is usually a

long history. Plantar fascia pain is degenerative in nature thus occurring over

time. An earlier treatment program will likely give a better prognosis.

· If you

would like to read some great articles on the science for and against bare foot

running go to the science of sport website www.sportsscientists.com

For those

interested in further reading Clinical Sports Medicine, Brukner and Khan, 2007,

have some excellent information and practical tips

For now,

Jimmy